By Peter Cohen, July 18, 2022

Image credit: Stephanie Lamphere, 2008, Community garden plots, via <https://flic.kr/p/5tvkR9>.

Are you an environmentalist, or do you work for a living?

This off-putting and somewhat condescending question was the basis for Richard White’s 1996 essay, where he used it to explore how American environmentalists saw their relationship to nature. He noted that many environmentalists knew nature through leisurely activities and saw work as an automatically destructive force, while others only considered archaic forms of work to be a valid and wholesome way of knowing nature, viewing modern forms of work as destructive.

White argued that both of these viewpoints were incorrect; you don’t need to be a tree hugger or use a mule-drawn plow to know nature, and that it’s through work – both archaic and modern – that we can build our relationship to nature.

With the climate crisis looming over our heads, knowing nature is more important than ever. We need to understand how delicate the earth’s natural systems are and how reliant we are on those systems in order to understand what’s at stake.

How can we gain that understanding if our relationship to nature is shallow, and is only defined by our own enjoyment and relaxation?

Having a casual, playful relationship with nature is good, but it doesn’t allow us to fully appreciate nature. Through work, we can cultivate a better understanding and appreciation of the environment around us.

To help you achieve this, I’ve compiled a list of ways that you can build a productive working relationship with nature, even if you live in an urban or suburban environment.

Urban foraging

Photo from Wikimedia on Pixabay. Pineappleweed, or wild chamomile. Native to Eastern Eurasia, it grows well in nutrient poor, compacted soil, and so can be found abundantly in many North American suburbs.

It doesn’t matter whether you live in the middle of a forest or in the middle of a concrete jungle, chances are that there are edible plants in your neighbourhood. Every day, you could be walking by a future entree that’s just waiting to be collected and cooked

Foraging can provide some interesting and tasty additions to your table, but will give you a more keen sense of the plants in your neighbourhood, boosting your awareness of nature by getting you into the habit of observing and searching for certain plants.

I’m definitely not an expert on foraging, and I rely heavily on online resources and my more knowledgeable friends. Some good resources include Seek by iNaturalist, which you can use to identify plants with your phone camera.

You can also check out Falling Fruit, a nonprofit aiming to document the locations and types of edible plants in local communities. The map can be used to find out which edible species are hanging around in your region.

I also follow educators on social media. One of my favourites is Alexis Nikole Nelson (@BlackForager on instagram and @alexisnikole on tik tok). Nikole shows off common plants that can be found in urban and suburban environments.

Each of her videos feature a different plant, and talks about recipes, cooking tips, and any look-alike plants to watch out for. Nikole started her pages at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, and aimed to show people how to supplement their groceries with foraged materials.

In addition to stretching out your grocery budget, gathering your food yourself gets rid of the mental disconnect between what you eat and where your food comes from.

In the same way that cooking your food gets you acquainted with the ingredients and gives you a better understanding of your meal, compared to ordering from a restaurant, gathering your food yourself gives you a better understanding of how your food grows when compared to buying it from a store.

I can personally vouch for foraging; I’ve enjoyed being able to munch on some sourgrass while I’m out gardening, or experiment and see how many different dishes I can make with dandelions. Still, it does involve going out of the comfort of the grocery store where everything is labeled, so caution should be exercised, both for your sake and for the sake of the environment.

Some important safety tips:

*Never eat anything if you aren’t absolutely sure what it is. That’s a good general rule for life, but it’s especially true if you’re foraging. Many edible plants have inedible or even toxic look-alikes, so it’s a good idea to refer to resources like the ones above.

*Avoid taking from lawns unless you know that pesticides haven’t been used.

*If it’s next to a road, avoid it, as plants next to busy roads can end up absorbing dangerous pollution from cars.

*Milkweed is tasty and can be cooked in a variety of ways, but avoid taking it unless there’s an abundance as it’s the only food that monarch butterfly caterpillars can eat.

*Don’t overharvest. I usually just take parts of plants, rarely the whole plant unless I’m after the plant’s root. As a general rule, you should never be taking so much of any plant that it won’t be able to replenish itself in that area – never raze, just lightly graze.

Manage a Veggie Garden

Photo by Kate Darmody on Unsplash

Whether it’s a single small herb in a pot, or a full veggie garden with an accompanying composting bin, working to cultivate the earth to produce something that’s useful to you is a very rewarding task. Even a single green onion that’s been placed in a cup of water and regrown can be a satisfying way to help keep the fridge stocked.

This goes a step further compared to gathering your own food. By involving yourself in your food’s growth, you can better appreciate everything that goes into keeping a plant alive.

When I’m tending to my family’s vegetable garden, I can quietly appreciate the fact that the plants I’m tending to exist in nature in some form, without human interference.

I can appreciate the fact that all of the things that I’m doing to keep a garden alive – the planting and sowing, the watering, the occasional use of fertilizer, and the management of pests – all of that happens in nature automatically, all in a way that allows the process to maintain itself and continue on, year after year. This also helps me to better understand the severity of climate change’s destabilizing impact.

Don’t worry if you don’t have access to a garden. Gardening is certainly doable, even if you live in an apartment building with little natural light. You can even compost indoors or on balconies with few to no concerns about unpleasant smells.

While gardening indoors somewhat limits the amount and types of food you can produce, it can liven up your home, improve your indoor air quality, and can be more convenient to maintain as you won’t have to worry about as many pests.

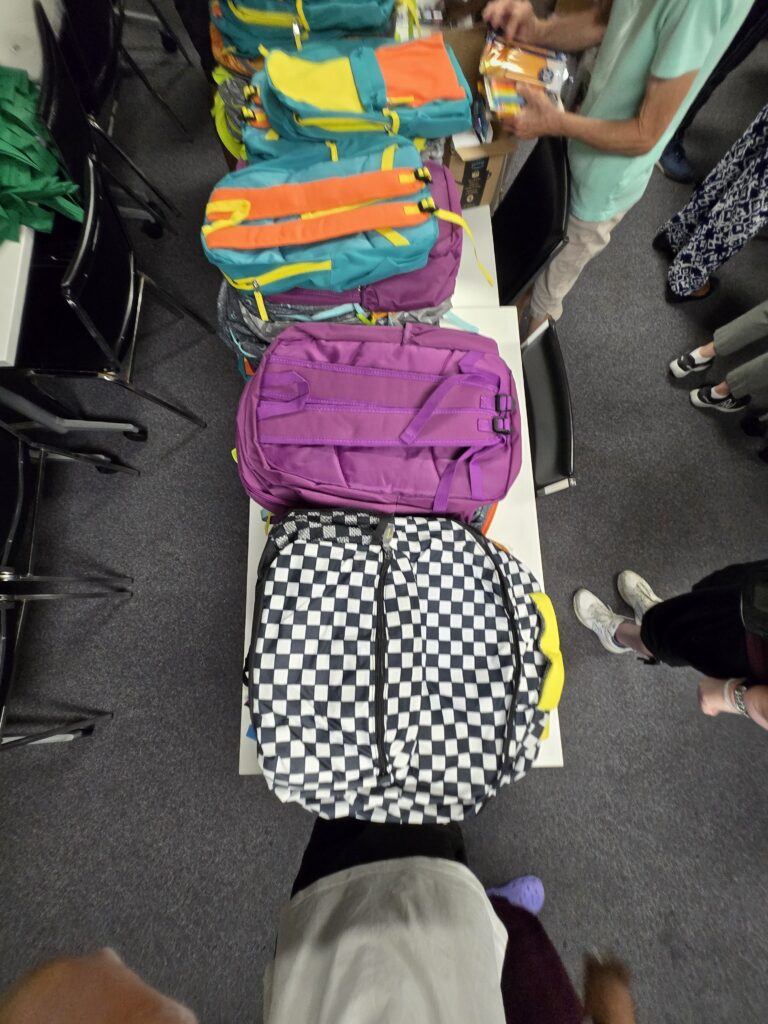

But having your own garden can be a lot of work, especially if you’re the only one caring for it, or have a larger garden. Luckily, volunteering with a local community garden is always an option, giving you the experience of gardening while sharing the work with others. For an added bonus, it gives you a chance to connect with people.

Even better, community gardens sometimes give part of their yield to foodbanks. It’s a great opportunity to connect with your community as you connect with nature, while also fighting food insecurity.

Contributing to nature

The previous items on this list have been ways that you can reap benefits from nature, with a focus on benefits for you and your community. And that’s not a bad thing, but the goal here is to have a relationship with nature, and any good relationship is defined not just by closeness and understanding, but by reciprocation. So how can you give back to nature?

Conservation and cleanups

Climate Justice Durham, 2019, results of a shoreline trash pickup, via <https://www.instagram.com/p/B3h2Mbont_r>

There are almost certainly conservation projects in your area. Restoration projects, wildlife parks, animal sanctuaries or shelters, and wildlife rehabilitation centers are always in need of volunteers.

You can also participate in community litter cleanups. Most towns have community cleanups planned by the town government or local environmental organizations. Some towns also provide resources to help you organize your own official cleanup, but there’s no rules saying that you need to go through official channels to organize a cleanup.

A community cleanup can just be you and a few friends going out to a field or creek on the weekend.

This guide is probably one of the most comprehensive guides I’ve found online, and contains a lot of good advice for organizing a community cleanup. This guide has additional safety tips that I highly recommend following.

Citizen science

Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

You can also participate in citizen science – research that relies partially or wholly on data collected by people who aren’t professional scientists. Research projects are often limited by budget or a lack of manpower. But with the help of ordinary people, under-resourced projects can get the data they need.

Some examples of citizen science projects include the ISeeChange app, which allows users to document climate change and how it’s impacting them. This helps scientists keep track of climate impacts in real time and gives us a collective climate journal.

There’s also the Caterpillar Count project. Participants document the amount of arthropods they can find, which helps researchers determine whether the insect population’s annual peak is properly synced up with when birds start to hatch, and whether these cycles are being affected by climate change.

Getting down on the ground level can give you a more nuanced understanding of nature and help you better comprehend the impacts of climate change, especially when you’re paying attention to nature’s cycles.

When you understand that birds end their migration and lay their eggs just in time for the insect population to peak as their eggs hatch, then you can understand why it’s a big deal when birds migrate earlier in the year, when plants bloom earlier or insect populations peak at different times in the year than usual. when

Altogether, participating in citizen science can deepen your understanding of the environment while also helping researchers monitor the state of the environment and gain a better understanding of how climate change is affecting our lives.

Thx

You’re welcome.